Memory coalescing in CUDA (1) – VecAdd

cuda basics techTable of Contents

Background

Memory coalescing is a crucial optimization technique in CUDA programming that allows optimal usage of the global memory bandwidth. When threads in the same warp running the same instruction access to consecutive locations in the global memory, the hardware can coalesce these accesses into a single transaction, significantly improving performance.

Coalescing memory access is vital for achieving high performance. Besides PCIe memory traffic, accessing global memory tends to be the largest bottleneck in GPU’s memory hierarchy. Non-coalesced memory access can lead to underutilization of memory bandwidth.

In the following post, we will delve deeper into memory coalescing with CUDA code for the classical vector adding.

VecAdd

There are three kernels in below. The complete code locates here.

Naive VecAdd kernel with memory coalescing enabled

The first program is simple but follows the coalescing memory access pattern:

| tid | element |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 3 |

| … | … |

The thread 0,1,2,3 visits elements 0,1,2,3, which is contiguous, and results in a coalescing memory accessing.

template <typename T>

__global__ void add_coalesced0(

const T* __restrict__ a,

const T* __restrict__ b,

T* __restrict__ c,

int n) {

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < n) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

}

The only issue is that, the number of the elements should be no larger than the number of threads, so the launching parameters of the kernel should be carefully designed.

Optimized one: strided with less threads

template <typename T>

__global__ void add_coalesced1(

const T* __restrict__ a,

const T* __restrict__ b,

T* __restrict__ c,

int N) {

int tid = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

int num_threads = blockDim.x * gridDim.x;

while (tid < N) {

c[tid] = a[tid] + b[tid];

tid += num_threads;

}

}

This one simplifies the calculation of the launch thread number, it should fit any number of elements with a arbitrary number of threads.

Uncoalesced memory accessing one

template <typename T>

__global__ void add_uncoalesced(

const T* __restrict__ a,

const T* __restrict__ b,

T* __restrict__ c,

int n) {

int tid = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

int num_threads = blockDim.x * gridDim.x;

int num_tasks = nvceil(n, num_threads);

for (int i = 0; i < num_tasks; ++i) {

int idx = tid * num_tasks + i;

if (idx < n) {

c[idx] = a[idx] + b[idx];

}

}

}

This one doesn’t follow the coalescing access pattern, lets assume that we have 4 threads with 8 elements, then the `num_tasks=2`

| tid | 0-th element | 1-st element |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | 6 | 7 |

In the first step of the for-loop, these four threads visit 0,2,4,6 elements, which is not contiguous, this results in an uncoalesced memory accessing.

Performance

All the kernels are tested with double data type, and the block size is 256, for the last kernels, each thread are setted to consume 8 elements. The performance is tested on GTX 3090, with the clocks locked as below:

| GPU clocks | Memory clocks |

|---|---|

| 2100 MHZ | 9501MHZ |

The latency of each kernel:

| kernel | latency |

|---|---|

| coalesced0 | 0.04 |

| coalesced1 | 0.04 |

| uncoalesced | 0.14 |

The uncoalesced kernel is 3x slower than the two coalesced kernel.

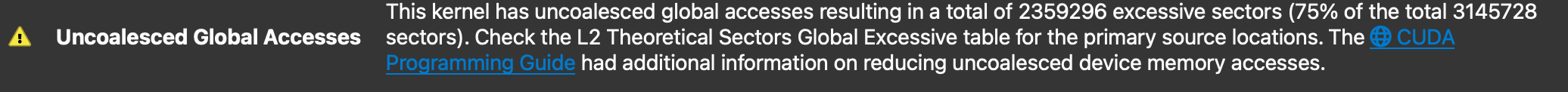

The Nsight also report the Uncoalescing Global Accesses in the uncoalesced kernel:

It reports that 75% of the sectors are excessive, IIUC, since only 8 bytes(a double) out each 32 byte transition is valid, so the overall efficiency is \(\frac{8}{32}=25\%\) .

References

- Professional CUDA C Programming